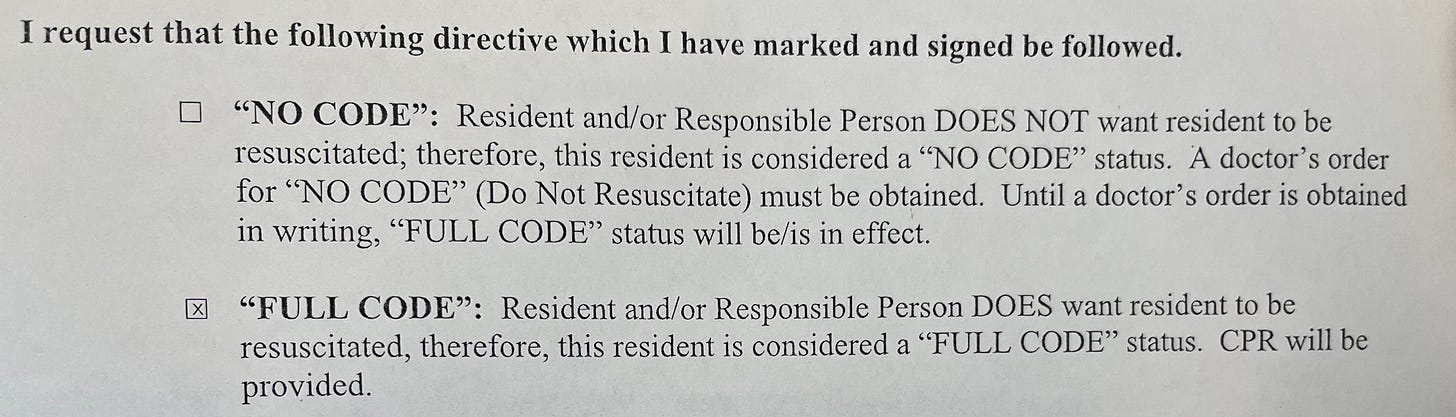

Full Code

I had my quarterly “life plan“ meeting today; it’s a time when the supervisory staff (nurse manager, social worker, dietitian, administration) meet with a resident (and their families or POA if appropriate) to check in on how things have been and to make sure everyone’s on the same page going forward. One of the points each time is to make sure everyone knows whether the resident is “no code” or “full code“ (a very important distinction in a facility like mine). When I was asked this question today, it reminded me of something I wrote more than a year ago (based on a memory from a year before that). I still think about it, particularly each time the question is asked, and when it came up today I decided that I’d also like to share it here, even though it is a fairly raw story. So here it is:

A story about June 13, 2023

A calm, firm voice (that I later knew as Dr. Lopez) leaned in close to me and asked me if I wanted my chart to say that I wanted to be full code, did I want heroic measures. I don’t actually remember her specific words, but I remember that the questions she asked seemed backwards, and I answered no, and she didn't like my answer. I understood what she was asking though – I had just spent 30 days in the ICU, and even just that morning had experienced unbearable pain as the team of medical folks had to peel the strong adhesive of my wound VAC off my very tender spinal incision, without pain medication. I cried, I screamed. I wanted to die.

And this wasn’t a new feeling. At some point on most of the last 31 days, from May 14 until now, I had wanted to die. It wasn’t about the paralysis, or the uncertainty or grief about what the rest of my life might be like. I know – and frequently argued – that people who have disabilities can live full and meaningful lives. But this wasn't about anticipating prejudice and other barriers that come from using a wheelchair, or worrying about hospital bills, or thinking about unfinished aspects of my job or the burden this was placing on my friends. In the last 31 days, I had experienced more fear, and pain, and horror than the whole rest of my life; if I told you all of it, you might have wished me the peace of death too.

And yet, not even 10 minutes before this question was asked of me, I had felt a primal craving to live – and not even a craving but a need, a desire, a mandate. If I hadn't just almost died – again – I would have been firm with my answer to Dr. Lopez. No, I do not want heroic measures; if my body starts to die again, please let it. Except…

That morning, when I left the ICU to transfer to Madonna, I was still on the ventilator. They had been working on weaning me off, but I wasn’t quite there yet, and so when they transferred me in the ambulance from Omaha to Lincoln, I was hooked to a small portable ventilator. The hour-long ride was tough – I was on a stretcher, and couldn’t communicate, and the ambulance (and I) felt every bump in the road – but I did visualizations, and imagined myself somewhere else, and eventually we arrived.

When they got me to Madonna, it felt like chaos. First the ambulance pulled up to the wrong entrance, and then, when they did find the right one, we had to travel through a number of dark under-construction hallways until we found the elevator to my new floor. It was not a great start, and I wondered where I was being dumped. We settled into a room – which I suppose was my room, but I could only see, or remember, the lights in the ceiling. A couple of people joined us there, and then more, and then more. Eventually there were at least a dozen people in my room, each seeming to have a specific thing they were trying to accomplish, all overlapping, and all at once. There were forms to sign (with an X, since that’s as much signing as I could do), there were blood draws, they were introductions, all while transferring me from the ambulance gurney to my new bed. In the midst of all this noise and chaos, they took me off of the ambulance air and put me on the Madonna ventilator. And suddenly, I couldn’t breathe. Something was wrong, very wrong. I was underwater, I was drowning. Here’s me who loves water; here’s me who had recently and also long ago imagined breathing water until I no longer existed on land, a peaceful transition. But this wasn’t breathing water – something was being forced down my throat, violently. It was brutal, it was torture, maybe it was waterboarding. In any case, it was a water that was contrary to my being, to my existence. All I could do was fight – I wasn’t thinking, I wasn’t reasoning. But I could fight; I had to fight. I didn’t have words then; I don’t have any words for this now. But some deep part of me was insistent, I had to fight. I could not, would not, must not die this way.

I couldn’t move much, beyond wiggling a few fingers, and I couldn’t speak or make any noise with the ventilator attached to my neck. I tried to express myself through my face, but no one was looking. All the people were going about their busy business, chatting and even laughing as they did the work they’ve done 1000 times before. Finally someone noticed me, and how “uncomfortable” I seemed, and someone else called out that my heart rate was high and my sats were dropping, and then eventually – I’m sure it was just a few seconds, but it felt like forever – someone asked if I was connected to the ventilator correctly. Another person replied that everything looked fine; in fact, they insisted that there was nothing wrong with the ventilator, it must be something else. But I kept not breathing. Someone asked if it was an anxiety attack and someone took my hand and tried to reassure me that I was OK. But I wasn’t OK. I was still here though; every bit of me struggling against the pull that was dragging me under. This felt so different from other times when I was resisting a pull to stop breathing– I wasn’t fighting it because I didn’t want to hurt my friends, or because my things weren’t yet “in order,” or any other rational argument in my head. This time I had no noises in my head, no voices playing both sides of an argument. It was clear and uncomplicated inside me; such a contrast to the chaos around me outside. I just wanted/needed to breathe, and to live.

And then someone yelled “code blue”, and all the conversations stopped. Just like on a television show, they took away all my pillows and pulled my head back, hard. There was a new flurry of activity around my body, moving cords and attaching things, some people coming forward and other people stepping back. I listened as they disconnected the ventilator tube and attached the breathing bag to the hole in my neck and squeezed a few times… and suddenly I could breathe again. I felt the life pouring back into my body; I was so relieved, and grateful, and could relax again. Air. They kept bagging me while the respiratory therapist continued to insist that the machine was fine, until someone with a firm voice convinced her to do a full reset – and only then did she discover that something about it hadn’t been working; it hadn’t been putting out any oxygen. An alarm had been going off the whole time, but apparently it’s similar to the alarm that goes off when a patient isn’t yet in their system, so everyone ignored it. She reset the machine, ran it through its diagnostics, and then connected the ventilator back to my throat. Air.

~~~

Dr. Lopez (who I only knew at that point as a calm, firm voice) leaned in close to me and asked her question, and my first answer displeased her. She asked me again, this time phrasing the question differently. Did I want my caregivers to do everything they could to try to save my life? This time I answered from the part of me that, without the ability to even think or reason, wanted fiercely to live, had just fought fiercely to live. Later my brain added to the story: I didn’t want to die just because a machine was malfunctioning or because someone was distracted at their job. But in that moment it was something other, something deeper, something primal, something solid. My answer was clear, oddly, because I had almost died again: yes, please try to save my life.

Thank you for that amazing story.

I'm amazed at the clarity of your reading of your own responses, under such stress.

I don’t even have words, Debbie.